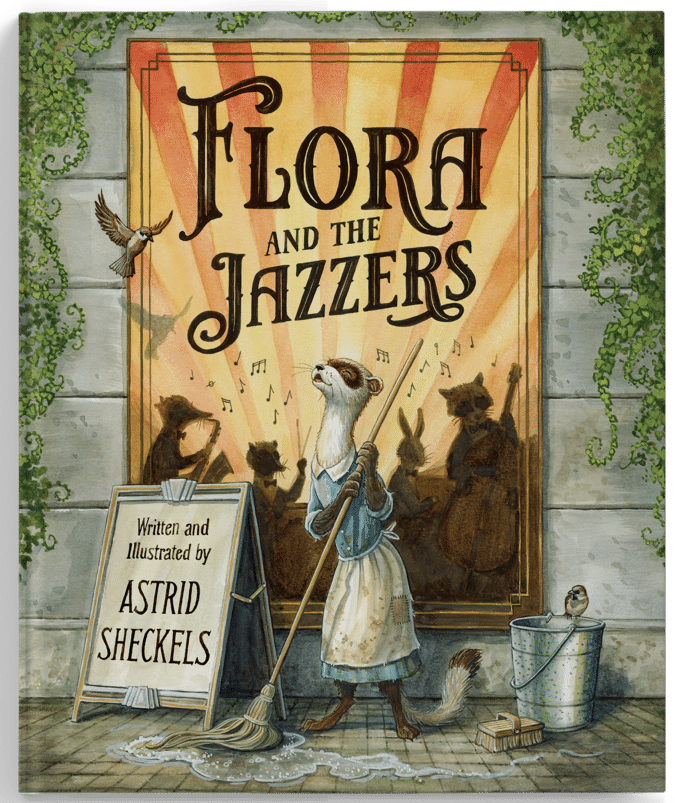

I'm recommending: Flora and the Jazzers by Astrid Shekels

A Classic Cinderella Tale in a Roaring Jazz Age Animal World

Flora and the Jazzers by Astrid Shekels is now available, Waxwing’s newest publication, and once again, I have the privilege to write about it here as part of my motley assortment of book reviews.

This is a Cinderella story.

What does that mean? The heart of a Cinderella story is that the underprivileged, long-suffering, usually virtuous female protagonist is given a leg up, and all her dreams come true, lifting her from the poverty she knows. The poverty may be material, but many stories reveal it is also familial. In more fleshed-out versions of the story, she is identified and chosen especially for her beauty, both inside and out. The virtues matter.

Flora is a ferret. In many hierarchies, we do not get much lower than that on the mammalian ladder. The ferret’s figure makes a perfect model for the setting and its Roaring 1920s fashion.

This is a picture book.

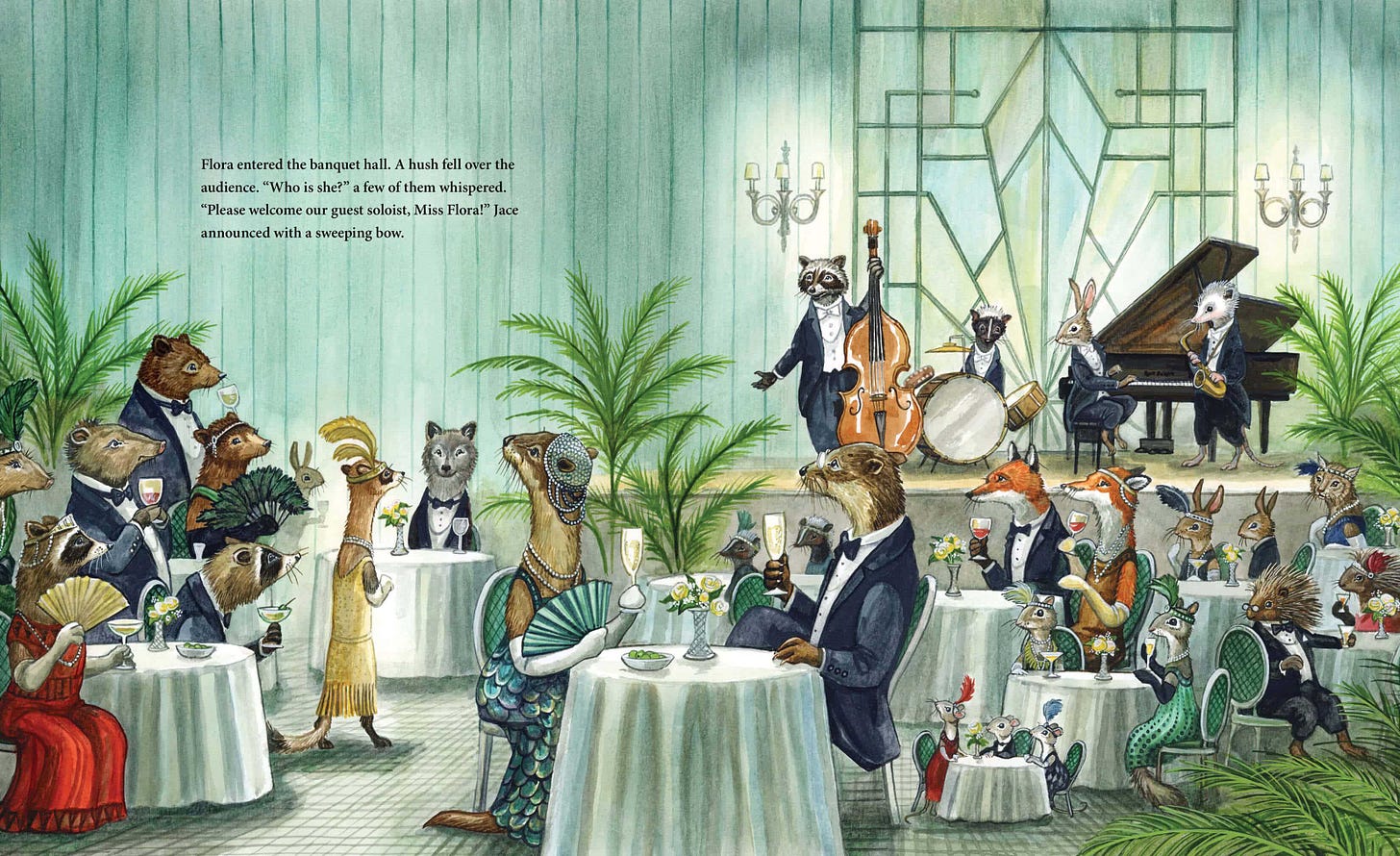

And the illustrations are lush! Oh my. Personality, humor, depth, color, joy, whimsy, serious fashion gravitas, and the deco, oh, the art deco! I watched a watercolor demonstration at ARCH art supplies in San Francisco, and the artist painted the dining room scene of a grand 1930s hotel. It was just like this.

I want to walk around these illustrations in real life. Art gallery in the lap, check.

The fashion, did I mention the fashion? This is my favorite historical time period. I am an avid old movie watcher. Shekels hit it just right. These are not the stereotypes of the time period; she captures the real thing. The costumes just happen to be draped on a variety of animalia instead of the rougher species of the era: the bootlegger and flapper.

What kind of ferret fairytale is this?

Fractured, or fleshed out, fairytales

The modern criticism of fairy tales, particularly the princess fairy tales, is that the reward comes too easily. Everything works out with the snap of the fingers for the protagonist. The Cinderella story by Perrault, from 1697, is as simple as it gets. As storytelling media evolve, writers try to answer the question: What motivates her? Why does she stay?

Flora is employed in the hotel. This is not a family affair. She is where she is for financial reasons.

“With a song in her heart…” Shekels describes and illustrates Flora’s inner life deftly and beautifully.

I like the newer versions of fairytales that still believe in the original story, but fill in the gaps. Grimm Brothers. The 2015 Disney live-action remake of Cinderella. The 1998 Ever After. Even the musical, Into the Woods, sits well with me for this story.

This is a traditional Perrault-style fairytale, swift in its telling, swift to its close.

I do not know how much this influences my enjoyment of this story, but I am married to a musician. The swift and happy ending came too easily for me.

If good narration brings us to a moment where all is lost, we care about the character and the resolution. I’m not sure I’m buying this retelling.

A well-known band would not be trying to work out a song the night of the performance; they would do a well-rehearsed set. They might add in new songs, but not that new, not so new that they did not realize vocals would be just the thing.

She has a song in her heart, but no vocal training, so it is unlikely that she would be such an immediate sensation, so much so that they are ready to sign her, then and there, and take her on tour.

There could have been more.

There could have been more. Maybe a little more of a backstory, so we know from where that experience came. Even the Phantom of the Opera wasn’t training up a blank slate.

Does Shekels know this, I wonder. Did she know she was bringing it in swiftly, and that’s part of the fun of a familiar story?

Some time has passed since our initial reading. There are books you read through, delighting in the language, holding your breath until that wonderful finish (An Orange for Frankie). There are books you read without interruption, ready to catch any joke (My Awesome Summer by P. Mantis). There are books you sing and laugh through, of which any interruption would spoil the rhythm (The Gruffalo). But there is another class of picture books. They are good. They are classic. They are in the canon of books I would not want to have missed. But they are strange. They are incomplete. They invite the commentary and the interruption and, dare I say, the humor of those reading them irreverently inserted.

My husband reads The Runaway Bunny as a horror story. The jokes are endless for us as well with Guess How Much I Love You. And yet we love these stories. As our oldest children entered their teens and new babies came again, we happily purchased them again.

They become part of us as we become part of the story. It’s a bit like The Neverending Story, I admit, but it becomes a beautiful shared secret among those who read it, with a chuckle and a sidelong glance that we know the real story —the story our silly parents read to us, the story our children tolerated as we read it aloud. They loved the picture; we loved the unity of an inside joke.

The illustrations: 100%. I would own this book for this reason alone.

The story: it fills the last category for me. I know there will be jokes, comments, insertions, and, hey, even some important conversations with my older children about how success and/or fame do not come easily.

Life is not a fairytale, although it speaks of the dream. It speaks to the truth of the dream. Sometimes, for a story, that is all we need.

This book is for:

The family led by a hopeless romantic who reads Jane Austen.

The family led by the artists.

The family looking for a simple, enjoyable read-aloud with beautiful language, that does not require long discussions, but invites it, the readers so wish.

Adorable, I miss reading picture books for myself from when I worked at the library, this one looks gorgeous!